Robert Altman's

GOSFORD PARK

GOSFORD PARK

USA Films

USA Films in association with

Capitol Films and the Film Council

A Sandcastle 5 production in

association with

Chicagofilms and Medusa Films

Producers: Robert Altman, Bob

Balaban, David Levy

Director: Robert Altman

Screenwriter: Julian Fellowes

Based on an idea by: Robert

Altman, Bob Balaban

Executive producers: Jane Barclay,

Sharon Harel, Robert Jones, Hannah Leader

Director of photography: Andrew

Dunn

Production designer: Stephen

Altman

Music: Patrick Doyle

Co-producers: Jane Frazer, Joshua

Astrachan

Costume designer: Jenny Beavan

Editor: Tim Squyres

Color/stereo

Running time -- 137 minutes

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Cast:

| Above Stairs:

Sir William McCordle: Michael

Gambon

Lady Sylvia McCordle: Kristin

Scott Thomas

Isobel McCordle: Camilla

Rutherford

Constance, Countess of Trentham:

Maggie

Smith

Raymond, Lord Stockbridge:

Charles

Dance

Louisa, Lady Stockbridge:

Geraldine

Somerville

Lieutenant Commander Anthony

Meredith: Tom Hollander

Lady Lavinia Meredith: Natasha

Wightman

The Hon. Freddie Nesbitt:

James

Wilby

Mabel Nesbitt: Claudie

Blakley

Laurence Fox Lord Rupert Standish:

Laurence Fox

Jeremy Blond: Trent Ford

Ivor Novello: Jeremy Northam

Morris Weissman: Bob Balaban |

Lady Lavinia Meredith, Lt. Cmdr. Anthony Meredith,

Morris Weissman, Ivor Novello

Constance, Countess of Trentham, with her

maid Mary

Macreachran

|

|

|

|

|

| Below Stairs:

Jennings -- The McCordles'

Butler: Alan Bates

Mrs. Wilson -- The Housekeeper:

Helen

Mirren

Mrs. Croft -- The Cook: Eileen

Atkins

Probert -- Sir William's Valet:

Derek

Jacobi

Elsie -- Head Housemaid: Emily

Watson

George -- First Footman: Richard

E. Grant

Arthur -- Second Footman:

Jeremy

Swift

Lewis -- Lady Sylvia's Maid:

Meg

Wynn Owen

Dorothy -- Still Room Maid:

Sophie

Thompson

Bertha -- Head Kitchen Maid:

Teresa

Churcher

Ellen -- Junior Kitchen Maid:

Sarah

Flind

Lottie -- Junior Kitchen Maid:

Lucy

Cohu

Janet -- Housemaid: Finty

Williams

May -- Housemaid: Emma

Buckley

Ethel -- Scullery Maid: Laura

Harling

Maud -- Scullery Maid: Tilly

Gerrard

Fred -- Bootboy: Gregor

Henderson Begg

|

Sir William McCordle with Head Housemaid Elsie and

First Footman George

Henry Denton (Morris Weissman's valet) and Mrs. Wilson,

the housekeeper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Visiting Servants:

Mary Macreachran -- Constance's

Maid: Kelly Macdonald

Robert Parks -- Raymond's

Valet: Clive Owen

Henry Denton -- Morris Weissman's

Valet: Ryan Phillippe

Renee -- Louisa's Maid: Joanna

Maude

Barnes -- Anthony's Valet:

Adrian

Scarborough

Sarah -- Lavinia's Maid: Frances

Low

Merriman -- Constance's Chaffeur:

John

Atterbury

Burkett -- Constance's Butler:

Frank

Thornton |

Robert Parks (Raymond's valet) and Mary Macreachran

(Constance's maid)

Lady Sylvia McCordle Henry Denton (Morris Weissman's

valet) |

| Outsiders:

Inspector Thompson: Stephen

Fry

Constable Dexter: Ron

Webster |

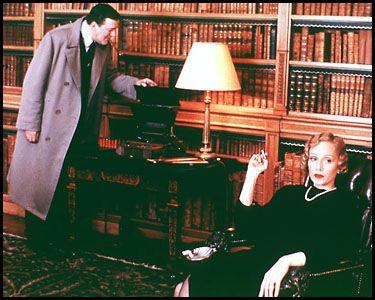

Inspector Thompson and Lady Sylvia McCordle

|

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Gosford Park

Review by Charles

Schoellenbach

Gosford Park is an entertainment and social

commentary that takes place at the estate of a wealthy English family in

1932. An overnight gathering of relatives and friends serves as a microcosm

for the English titled nobility, including their servants. The audience

is sort of an invisible guest that takes in the little dramas, the off-handed

remarks and the snide insults that are a part of this world of genteel

contention. We are not told what is happening, but better, see it for ourselves,

as if one were peeling away linen from a bed, starting with the bed cover

and working down to the sheets. The movie is so busy with the many characters

and their intertwined lives, it is unclear where the story is going, but

by the end of the film, the pieces have come together. Not too many films

enjoy the process of discovering the subtle workings of people’s lives

as this one does. Gosford Park is a comedy of manners that works on several

levels—it is a murder mystery and a tart satire of the upper class, ending

as a satisfying film.

Sir William McCordle (Michael Gambon) and his

younger wife Lady Sylvia McCordle (Kristin Scott Thomas) are hosts to a

three-day affair at their mansion. Accompanying the guests are their maids

and valets who will share the downstairs servant’s quarters with the McCordle’s

servants. It is the fight that each guest wages to protect their social

and economic standing that drives the story, along with the pretence that

the people who are residing upstairs in the mansion have nothing to do

with the servants living downstairs, beyond each one’s clearly delineated

roles. The film examines each relationship through the master-servant theme

that is the connective tissue of the story. Hypocrisy, snobbery, adultery,

malice and intrigue prevail. Those who claim some association to English

nobility, be it contrived or not, are for the most part rude and pretentious

and incapable of surviving on their own without a satisfactory inheritance

or the golden touch of a benefactor such as Sir William. Otherwise, they

marry into wealth. Ironically, the relationship to their servants, whom

they look down upon but could not live without, runs deeper than this aristocratic

group can imagine.

The story shifts throughout the film between

the upper floors and the servant’s hall, interweaving the two until it

is only a deceit that separates them. The movie does not keep the servants

sequestered downstairs until the guests need them. They are not shadows,

but real people, with lives their employers never acknowledge, let alone

are able to comprehend. Once the guests show up, each strata kicks into

gear. Above, the guests work out the pecking order, as do the servants

in a mirrored mockery below. Jennings (Alan Bates), the Gosford Park’s

patriarchal and stuffy butler, stands present beside the McCordles as they

greet the arrivals. At dinner, he rigidly enforces the seating precedence

at the servant’s dining table, so that it reflects the rules of protocol

practiced upstairs. Constance, Countess of Trentham (Maggie Smith) an outspoken

and nasty-tongued snob arrives with her recently hired, pure-as-milk, Scottish

maid Mary Macreachran (Kelly Macdonald). Mary is slightly overwhelmed amidst

the controlled pandemonium as Mrs. Wilson (Helen Mirren), the no nonsense

Housekeeper and one of the triumvirate that manages the servants, tells

her she will share the room of the Head Housemaid, Elsie (Emily Watson),

a cheeky woman among the servants, who befriends Mary.

Upstairs, The Honorable Freddie Nesbitt (the

title is a humorous stab), played by James Wilby, arrives with his wife

Mabel Nesbitt (Claudie Blakley). Freddie is an unabashed sponger who directs

at Mabel ugly fits of impatience and anger because Mabel’s money has run

out, causing him to beg for handouts from both Sir William and William’s

neurotic daughter, Isobel McCordle (Camilla Rutherford) with whom he shares

a past entanglement. Because the Nesbitts are so low on cash, they cannot

afford a maid for Mabel and must accept the temporary services of Emily,

the Housemaid. After a row between Freddie and Mabel, Emily helps Mabel

with her hair to “make her look respectable”, as Freddie put it. Those

with less power form tenuous alliances if it is only to provide comfort

to one another during their times of misfortune. The short in stature as

well as size Lieutenant Commander Anthony Meredith (Tom Hollander), accompanied

by his wife Lady Lavinia Meredith (Natasha Wightman), is also scrambling

for William’s financial favoritism. Others who are comfortable in their

positions, or who are merely complacent, enjoy the party for the social

diversion it provides. Taking pot shots at others, catching up on gossip

and doing some pheasant hunting are the favored activities. Most everyone

is dismissive of the American film producer, Morris Weissman, played by

Bob Balaban. The people at the party treat Weissman like a package sent

to the wrong address. He got himself invited through his friend, Hollywood

actor, Ivor Novello (Jeremy Northam). Henry (Brian Phillipe), Morris’ recalcitrant

valet with a bad Scottish accent is an example of what happens when a person

crosses class boundaries.

A pheasant hunt at the Gosford Park estate

serves as a metaphor for the inbred hostility that exists among the guests.

Indoors, the sport of choice among this group is to find someone at a disadvantage

and take a shot. Social standing is a common target. The stuffy military

man Lord Stockbridge (Charles Dance) sniffs a condescending response to

Mabel’s mentioning that her mother was a teacher. Ivor Novello, who was

listening to the exchange, sniffs back at Stockbridge as he walks away

from him that Novello’s mother was a teacher as well. No one thin-skinned

could survive long amidst the biting remarks flying through the air. Everyone

knows what is going on in everyone else’s life, so it is not too difficult

to find a vulnerable spot to aim at. Humiliating someone in front of the

guests, causing that person to slip off their pedestal, is a coveted prize.

The center of this world is the host, Sir William,

who has a tight grip on the purse strings, not hesitating to tug at them,

or cut them, on a whim. William has an established reputation, among the

guests and servants. If his satellites do not despise him, they put up

with him because their financial well-being depends upon it. William is

a boor who talks with food sticking out of his mouth and feeds his ever-present

lap dog at the table. The world does not extend beyond his hedonistic desires

for food, sex and power, though a tiny capacity for warmth towards others,

which he never bothered to develop in his life, seeps out through the cracks.

Otherwise, as far as he is concerned, playing a not too bright manipulator

is an entitlement, as it is a distraction with which to fend off boredom.

The people this patriarch has gathered around him fulfill the prophesy

of his disdain. They are not capable of doing much else except scheming

ways to wheedle money and secure a position.

The servants, on the other hand, are maneuvering

in a gloomy labyrinth. Just like their quarters, they live in a world below

the rest that requires acumen and resiliency to get along. The cliché,

that the servants know more than those they work for, is not just a story

device; it is an important theme in the film, examined from several aspects.

Gossip has a two-fold importance in this milieu. Constance encourages Mary

to tell her the gossip she hears from the other servants for its entertainment

value. Gossip also allows a servant to imagine a sense of control in a

world where he or she has little (not to mention living vicariously through

the aristocracy) and even provide information that might help to keep one’s

job. The consequence of a servant losing their job is not cataclysmic,

but they have less to fall back on than any of the upper class. The master-servant

relationships in the sexual liaisons—those that are ordained, and those

that are not—get a close look, too. Only once do a man and a woman stand

as equals, and that is after the realization of love following a comical

conversation. Everywhere else, as much sweat and blood flow from the wrangling

for power as in the actual sex act. Solace exists for the wounded, but

it is a woman who provides it, and usually to another woman. In this arena

the weak join forces, but they do not do much more than commiserate. Rising

above one’s station is near impossible. For all intents and purposes, the

position a person is born with is theirs until they die.

The lingering close-ups of the bottles of poison

that sit quietly on shelves in various parts of the house are a funny melodramatic

touch. In any other film it would be clumsy, but Altman weaves the foreshadowing

of events, together with the depicting a world that eventually corrupts

those it comes in contact with. At the beginning, we are not sure if Altman

is making a symbolic statement or if the poisons are like potential weapons,

forgotten but quietly waiting to stir someone’s imagination. Perhaps both?

As in Cookie's Fortune, and also Dr. T and the Women, Altman is fascinated

with relationships to create a lens through which to look at the characters

from several angles. When a murder is committed in Gosford Park, the act

makes all the sense, but not for the reasons we think. Mary, Constance’s

innocent maid, begins to see her world in a new dark light. Her need for

answers turns her into her own detective, for she knows of things that

the inept Inspector Thompson (Stephen Fry), who is investigating the crime,

has not the slightest clue. Mary’s emphatically held, but naïve, notions

that she lives in a basically good world are threatened. She cannot stop

until she finds the truth, and when she does it changes her forever.

Altman’s film carries on a tradition of social

commentary costumed as a cinematic distraction much like Jean Renoir’s

Rules of the Game. Gosford Park is not a great film. It is speckled with

little flaws, like the missing payoff scene after Anthony Meredith’s revelation

of love. Also, Mrs. Harris’ comment that servants are of ultimately no

importance, although true, is a self-pitying and heavy-handed line that

aches for dry restraint. Freddie Nesbitt and Anthony Meredith, who are

both trying to get money out of William, are too much alike—their situations

and their characters are redundant. The movie’s story is such a kaleidoscope

of personalities and sub-plots that it practically clatters like the shutter

inside an old motion picture camera. And, there are others. But these faults

are not detrimental, and do not really matter. Altman so much relishes

putting together this drama using the connective tissue of greed, sex and

the desire for power, you cannot help but be delighted, and affected by

his work. This is a movie about the pleasure of seeing a story unfold.

The sentiments between the participants are each delicately strained to

reveal the pain they all share to some degree or another, caused by the

destructiveness of this caste system they live with. This is what makes

watching Gosford Park such a treat. Why cannot more movies be like this

one?

This review written in 2002 courtesy

of Charles Schoellenbachs's

Sex,

Bullets & Popcorn Movie Review

Web Site